Welcome to the discussion! We thought we'd start this conversation by looking at why partnerships and coalitions are important to human rights work, and why they are hard to do. Consider these questions below when sharing your comments in this discussion topic:

- Why is it important for human rights groups to build partnerships and/or coalitions around their issue/movement? What are the specific benefits that come from this kind of collaboration?

- Is there a difference between partnerships and coalitions? If so, what is the difference and why are they important to differentiate?

- Why is it hard to develop these kinds of partnerships and coalitions? What are the barriers that get in the way?

Share your thoughts, experiences, questions, challenges and ideas by replying to the comments below.

For help on how to participate in this conversation, please visit these online instructions. New feature: you can now add images and video to your comments!

Hello all,

I'd like to share some of the key difficulties i've come up against when developing partnerships.

It would be great to know if others others have come up against these problems and found solutions. Or if there are other difficulties your experiencing that we can add to the list of those we're aiming to work through?

There are two main difficulties that I often face in developing effective partnerships:

Firstly; Although the different parties tend to be aligned in their overarching goals (e.g. women's rights) their specific aims tend to be different (e.g. each party is focusing on the rights of women in different countries, or even different aspects of law relating to women’s rights within the same country or issue area). This tends to weaken the partnership outcomes because each partner is understandably concerned over the other taking the focus away from their aims.

Secondly; Time. This is a problem on a number of levels. By the time an individual organisation’s planning has reached the stage of looking for partnerships on an issues / campaign area, they have already identified their main aims and the time they have left to reach their goals tends to be quite short, in some cases 3 to 6 months. Usually this is the result of external key moments in time which are immovable.

In order to address this I have often considered establishing a regular meeting point / coalition or sorts with similar orgs. The aim would be to keep us abreast of each others future plans in the hope we can better align ourselves. The problem i've found with this is that it requires myself and others to priorities time to meet regularly without having a specific outcome in mind other than the hope that we might happen across areas of mutual interest in time to work more closely together. While this is a valuable aim, prioritizing this over other things is difficult. Has anyone established something like this and if so was it successful enough to make the time worth while?

Cheers,

Anouska Teunen

Thanks for starting out this discussion on barriers to partnerships & coalitions! I recently found some great information on coalition-building for change on the Community Tool Box website (a project of the University of Kansas). Here is a list of barriers that are listed in this toolbox - it would be great to hear about the experiences of participants in this discussion regarding these barriers.

Have you experienced these barriers in coalition-building? How did you overcome them?

- Kristin Antin, New Tactics Online Community Builder

In our area Domination by professionals/elites is a real problem. Probably it is because of paternalistic culture (we believe in the reality of "big people" differentiated from "peasants", etc). But also the introduction of professional life through the colonial days has created large classism which runs through the nonprofit sector so much so that NGOs and national organisations refuse to work with CBOs and local communities. Often this refusal is only because of one person at a top office, not the choice of all the staff of an organisation, which means there are internal factors to this problem (for example, if we changed the hiring process to survey values and ethics as much as CV credentials, it could help eliminate this issue over time).

Another problem exists from the view of CBOs and churches. They often want to partner with everybody in hopes of obtaining more funds, but partnering with anyone and everyone is not a good way to achieve goals or even have a relationship where everybody benefits. Moreover the larger organisations and funders will not take the CBOs seriously if their approach is to continue this kind of dependency.

Does anybody have any stories or advice from overcoming the professional barriers?

I definitely agree with you, Solidarity Uganda. I work for an international NGO whose job is to connect larger international NGOs and the international community (governments, EU, UN) to the "little guys" - community leaders, presidents of small local NGOs, individual activists etc. I take to heart what Allison Cesr said (see her commment below). Everyone in your sector needs to consider their "value added." The big guys might have more money, but it's the on-the-ground activists who control the flow of information. In my sector, if we didn't have that information, what the big guys did with their money wouldn't matter. Make sure that the decision-makers understand who is providing this local information, and why they need it to continue their work. Create opportunities for local staff to prove themselves, even if they don't have a fancy CV.

As for effective partnerships with those bigger organizations - work with your donors to get funds that don't just fund a single project, but help you with capacity building and increase your ability to expand the scope of your organization. Those one-off projects might be more attractive, but the capacity building will get your organization to the next level and reduce dependability on outside funds. Maybe you can even use the funds to teach your more passionate, local staff the "professional" skills they need to compete in the industry.

Thanks Kristin, for sharing the Tool Box. Also thanks to the collegaue from Uganda, I can imagine a similar problem might exist here in Kenya (though not sure, would like to hear if so!).

I would like to introduce another dynamic. A special kind of alliance, or partnership (am keen to see the discussion about the difference between the two!), is that between an international NGO and their local counterparts, or phrased the other way around: between a local NGO and its international counterpart (funny how it is usually phrased the first way!). The international NGO can give credibility to the local one, and can give it security - because it can tap into the global media and can more easily mobilize international attention. Also, the international partner will often have more resources.

On the other hand, the international partner can be 'pushy' in its agenda, for its own (international) interests or objectives. Also, sometimes the international partner becomes like a big brother, who takes the local one (the younger sibling) 'by the hand', which is sometimes quite inappropriate.

I have the impression there is a lot to learn for the 'big ones', about how they can improve their support and cooperation with local groups, such that they mutually benefit and gain in impact. Am keen to hear about experiences and lessons learnt!

Thanks for sharing these points, Anneke! I wanted to pick up on your point around the potential benefits of partnerships between international and local NGOs (credibility, resource-sharing, and mobilizing international attention). I found an interesting essay on Beyond Intractibility about coalition-building and I wanted to share the list of coalition benefits that are listed in this essay:

Do these coalition benefits resonate with you? Which ones? Are there others to add to this list? Share your thoughts and experiences by clicking on the 'reply' button in the bottom right corner of this comment. Thanks!

- Kristin Antin, New Tactics Online Community Builder

I thought this was a great video from the Human Rights Campaign that explains from their perspective why coalition building is so important in their work.

Cuc Vu, Chief Diversity Officer at the Human Rights Campaign, has years of experience in the labor and LGBT rights movement. An essential part of her job is uniting groups focused seemingly different issues to build power for our common cause: equality and justice.

At the heart of her message, she says "We can't win it alone."

In this video, Dr. Sami al-Arian gave his thoughts on effective coalition-building for social change. He says, as an activist you need power to reach your goal. You build coalitions because you are asking demands of people with power to change what they are doing by either benefiting them or hurting them. But you need the power to acheive both....thus, coalitions are formed to build power through numbers to benefit (ex: we'll vote for you) or hurt your adversary (ex: we won't buy your stuff).

Thoughts?

- Kristin Antin, New Tactics Online Community Builder

I'd add a resounding endorsement to the point that working in coalitions and partnerships can bring expertise to bear on complex issues! I'd also add that such expertise doesn't necessarily come from within the human rights community -- interdisciplinary partnerships can be particularly fruitful and open up opportunities for innovative research and advocacy. For example, CESR worked with a coalition of NGOs and civil society organizations to examine the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights in the wake of Spain's economic crisis. The coalition included the Spanish Union of Tax Inspectors (GESTHA), who was able to estimate the resources that could be generated by combating tax evasion. This helped to substantiate the argument that the government was not dedicating maximum available resources to preventing retrogressions of these rights, a key requirement under the international Covenant (see e.g. figs 18 and 19 of CESR's Factsheet on Spain). It'd be great to hear other experiences of working with partners from other disciplines.

Thanks for starting this conversation off with such a rich trove of resources! I'm glad Allison mentioned interdisciplinary allies and would like to follow up on that. I work with the Science and Human Rights Coalition, a network of science and engineering societies (including my employer, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which serves as the Coalition's Secretariat) that recognize the important role for science and technology in advancing human rights. The Coalition is inherently interdisciplinary -- building bridges between the scitech communities and human rights communities, but also creating alliances across different science and engineering fields, with human rights as their shared core value.

In the five years since the Coalition launched, the Coalition has accomplished very positive results that would not otherwise have been possible. Coalition member organizations have shared ideas and best practices with each other, and have combined their talents on joint projects that benefit all of the members. The Coalition has also created peer-to-peer mentoring opportunities that might have been difficult for members to cultivate otherwise. As a result, the Coalition's membership has grown to 51 member and affiliated organizations. As this conversation on coalitions and partnerships evolves this week, I'll share some resources that have been important elements of the Coalition's progress. Some of those were developed at the outset by forward thinkers. Others were created to address concerns as they arose. All of them are available on the Coalition's website, http://www.aaas.org/coalition (transparency being a core value of the Coalition's work).

One of the challenges along the way has been framing and language differences. The ways scientists and engineers approach a project often differs from the approach used by human rights advocates. That goes for different types of scientists too: ecologists, sociologists, physicists, chemists, statisticians -- they all have their own "jargon" and their own ways of analyzing problems. Most of the time this is not a huge obstacle; people who respect each other and have shared goals are usually able to talk through the types of misunderstandings that sometimes come up in any coalition. But from time to time it becomes necessary for members of a team who have very different backgrounds to take a step back and work to understand why others might see the task differently.

Are there best practices (or lessons learned) for effective communication within interdisciplinary groups?

Thank you Allison and Theresa for sharing these examples of how experts can contribute (as partners) to the efforts of human rights defenders. Beautiful Trouble has some advice regarding activists working with experts. They write:

Experts can be terribly helpful co-conspirators and there are plenty of them out there to befriend. So go ask one for help.

...

But beware of getting too comfortable in the role of expert. Remain tactical. Construct your environment and apply pressure as needed. If your job is done or the project has run its course, then don’t linger at the mic. Reap the benefits of acting fast and freely, then disappear. Experts have made a long-term commitment and are good at sustainability; they choose their territory and stick it out, for better or worse. Activists and experts are simpatico but not interchangeable.

Good advice? Does this resonate with you?

- Kristin Antin, New Tactics Online Community Builder

Interesting points! I think becoming "the expert" is context-specific. It very much depends on who our audience is and how they're likely to be persuaded. For example, when we were advocating before the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see comment #18), for example, we needed to present ourselves as experts to present an authoritative counter narrative to the government’s report. Similarly, if the audience is judges or parliamentarians, we need to speak their language. Independent experts are really important here, as outlined in the guidelines that Theresa shared (see comment #7); they are perceived to be objective and impartial, whereas a human rights NGO is perceived to have an agenda. When our audience is civil society groups, or social movements or the public generally and our objective the mobilization of support and activism, however, then I think Beautiful Trouble’s advice is spot on.

If we come to think of those with formal, specialized education only as "the experts," then Beautiful Trouble has a point. If we apply that thinking to experts with non-formal education or with cultural or experience-based knowledge, then that type of thinking is toxic and corrosive to any partnership.

Having worked on the academic side and now on the community-based side of human rights work (not that these are exclusive), I know intellectually and by experience that experts exist on both sides. We don't often think of or value experienced-based or non-technical ways of knowing as forms of expertise. It's a condition of western societies largely, and it's part of the root of the problem to developing effective partnerships.

Especially for organizations on the frontline of struggle, who themselves have been objects of study for such "experts," they are aware of the perception that they are not experts themselves, but resources be mined. This breeds distrust and resentment that obstructs the path to effective partnerships when an outside partner (such as an international or national NGO, or anyone outside of their circle) comes knocking. If felt unacknowledged and unaddressed, these dynamics becomes toxic to developing an effective partnership. (These unrecognized experts might join the partnership for capacity and resource purposes, but not because they think you see them as equals at the table.)

For these reasons and others, we have to expand our conception of who we label "the expert;" and strategically deploy the term to include people(s) and communities that have experienced-based and cultural forms knowledge or expertise. This has been a particularly effective way of building partnerships for my larger, national organization that works with and aims to work with historically marginalized, community-based, and frontline organizations.

Excellent point, Yolande - thanks for sharing this.

- Kristin Antin, New Tactics Online Community Builder

Anneke, I'm so glad you raised this issue of how to manage the dynamic in the context of partnerships between national and international NGOs. I work with an international NGO and it's a crucially important issue for us. In particular, we’re very conscious of the need to maintain equal partnerships with the national NGOs we work with; as you rightly point out, there’s often a tendency for international NGOs to become overbearing! Broadly speaking, we try to do this by:

Perhaps there’s a broader point to be made about need to clearly define the strategic objectives of working in partnerships (or coalitions). It would be great to hear if any other organizations -- national and international -- have more formally established protocols or criteria for determining when to enter into partnerships or coalitions?

Great point and inspiring by Anneke.

How ever is partnership more than relationships and dialogue? who defines the partnership guidelines and how the agenda is run? many local organizations depend on support in form of funding based on criteria developed by the later international organizations so where does the partrnership end or begin within local beneficiaries and organizations?

i like this debate

Hi!

I'm not sure if this discussion is still on but I agree with rapudo both that it's very interesting, and that sadly issues of funding can complicate both partnerships ("if we coordinate too well our organisation might not have an added value") and the direction of what is in fact being done. The lack of agreement on objectives, in my experience, is all too often linked to where money is coming from for different actors, in particular where international aid funding is involved.

Thanks for adding this comment, Helena! Securing your added value to a partnership is important and challenging - and yes, where the money is coming from can add lots of complexity and competition. I hope others will add to this discussion.

- Kristin Antin, New Tactics Online Community Builder

What is the difference between partnerships and coalitions? Are coalitions simply a type of partnership? Here are a few definitions of 'coalition' that I have found online:

A coalition is a temporary alliance or partnering of groups in order to achieve a common purpose or to engage in joint activity. [Douglas H. Yarn, The Dictionary of Conflict Resolution. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1991), 81. Found on Beyond Intractibility website]

In simplest terms, a coalition is a group of individuals and/or organizations with a common interest who agree to work together toward a common goal. That goal could be as narrow as obtaining funding for a specific intervention, or as broad as trying to improve permanently the overall quality of life for most people in the community. By the same token, the individuals and organizations involved might be drawn from a narrow area of interest, or might include representatives of nearly every segment of the community, depending upon the breadth of the issue.

Coalitions may be loose associations in which members work for a short time to achieve a specific goal, and then disband. They may also become organizations in themselves, with governing bodies, particular community responsibilities, funding, and permanence. They may draw from a community, a region, a state, or even the nation as a whole (the National Coalition to Ban Handguns, for instance). Regardless of their size and structure, they exist to create and/or support efforts to reach a particular set of goals. [Found on the Community Toolbox website]

In terms of human rights 'partnerships', I see this term as the most broad way to describe 2 or more groups working together on a specific aim. IT does not need to be formal and the existance of the partnership is not necessarily public knowledge (nor would it help anyone if it was). Whereas a coalition might depend more on having a public identity because its strength is in its numbers (often).

What do you think? Please share your ideas and thoughts on these definitions by clicking on the 'Reply' button in the bottom right corner of this comment. Thanks!

- Kristin Antin, New Tactics Online Community Builder

It would be great to tease out this definitional question a bit more. Picking up from Kristin’s definitions above, here are a few observations on the distinctions between coalitions and partnerships:

These observations are based purely on my experiences with CESR, so of course they may or may not resonate with others! Look forward to hearing your reactions.

The obvious next question is ‘so what’? Do these distinctions matter in terms of understanding the benefits and challenges of each? I think the formality question does make a big difference. Some of the challenges around managing expectations (e.g. around visibly and branding, as Sophie rightly highlights in comment #21) are more pronounced for coalitions. These issues aren’t often explicitly spelled-out when the coalition is being formed. So the opportunity to negotiate clear parameters is a real advantage for partnerships.

That said, Rapudo makes an important point (comment #13) about who has the power to determine the agenda and who sets the criteria for determining if an organization is eligible for a partnership? Where a partnership has financial implications, it’s often the organization with the money! Perhaps there are other local organizations that have experienced this dynamic and have been successful in “pushing back” against partnership terms that they didn’t feel were beneficial?

I work for a global organization that partners with local and national level groups on legal advocacy projects that advance women's rights. Most of my work is in the U.S., but the dynamics between an organization working nationally/globally and one working at a local or state level in U.S. states echo a lot of the concerns and issues raised in this discussion. I agree with a lot of what's been said so far.

Below are some questions I try to ask myself when entering into a partnership with another group, based on what's worked and what hasn't in past partnerships. They may overlap with issues specific to coalitions, but I really have partnerships in mind here (more on that distinction later).

Katrina,

I totally agree and greatly appreciate the way in which you framed these questions. We have identified general principles in our work with partners:

I also ran across this interesting slideshow on "Learning in Partnerships", by Bruce Britton and Olivier Serrat (from a development / business perspective) http://www.slideshare.net/Celcius233/learning-in-partnerships

The following definition and key points about "why enter a partnership" resonated with our New Tactics experience when developing partnerships with organizations in other countries. I would be interested to know what you and others think of this model doing national/international work.

Definition:

A partnership is a dynamic relationship pursuing joint goals and objectives through shared understanding of the most rational division of labor based on the comparative advantages of each partner.

A partnership balances organizational identify and mutuality in a reciprocal framework of respect, decision-making, accountability, and transparency.

Why enter into partnerships?

Hello, All.

This is my first time participating in a dialog --thanks for raising this question! I'm already finding new resources and ideas. Thank you.

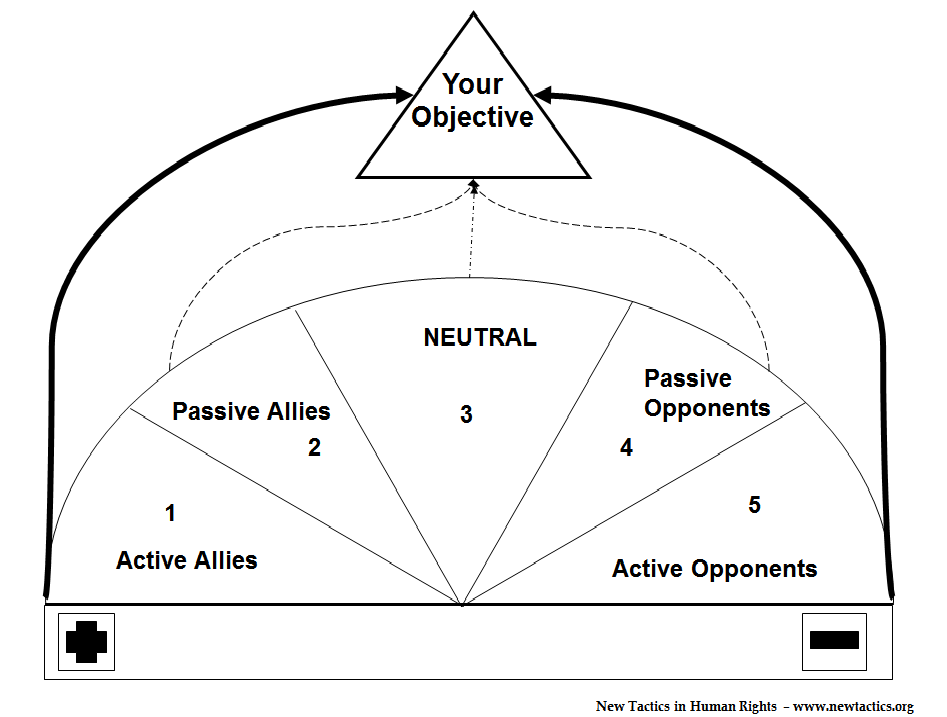

I was at a workshop facilitated George Lakey [1] a few years ago where he used "spectrum of allies" [2] to get us thinking about coalitions in a new way. I have since used variations of this activity with community groups (as a guest facilitator) and with students (as an instructor). I think it's useful --especially when (a) I'm facilitating a small group and learning about the conflict at the same time; (b) when a group gets stuck in a "they're with us or they're against us" mentality; and / or (c) when a group feels lost and wants to step back to reflect on context. It is very, very simple (a plus in my book).

That being said, I've also found that coalitions can be tricky and time consuming for many of the reasons already posted (lack of trust, perceived scarcity of resources, turf, strong personalities, disabling elites [3], bad history, etc.). Forming coalitions across class and race have been particularly difficult. My experience has been that up front conflict resolution work (managing parties expectations, negotiating clear roles, talking with the parties about how they want to talk to each other, figuring out what parties need in terms of how the coalition will be presented publicly, etc.) is really important. It's also been my experience that coalitions need constant support and maintenance.

One question on my mind now --and I hope that someone here can help me to learn more about it --is what to do in a situation where groups might want to cooperate but one or more do not want to be seen as doing so publicly. I suspect that this happens frequently but is not recognized as such. It might be misinterpreted by potential allies as a simple refusal to cooperate (when it really is a refusal to be seen cooperating). I know from experience that groups waging pressure campaigns against individuals or small organizations can sometimes get more of what they want (and sooner) if they promise not to declare victory or otherwise make a big stink about it. This "face saving" can make it cheaper for them to concede on something. I'm wondering now if the same principle could be applied to forming coalitions, but in reverse: maybe in certain circumstances offering confidentiality to potential allies might bring in someone new.

Any thoughts?

[1] http://wagingnonviolence.org/author/georgelakey/

[2] http://www.trainingforchange.org/spectrum_of_allies

[3] http://www.uvm.edu/~asnider/Ivan_Illich/Ivan_Illich_Disabling_Profession...

Jesse,

Welcome and thanks for joining the discussion!

I totally agree that the "spectrum of allies" is a GREAT tool for helping organizations to identify allies and potential coalition members. New Tactics adapted the Training for Change spectrum from 7 segments to 5 segments which has been enthusiastically received by activists in many countries where we have shared it in our trainings. Here is a diagram of our adaptation.

Regarding your question "what to do in a situation where groups might want to cooperate but one or more do not want to be seen as doing so publicly?"

In my opinion, a critical and essential aspect to address is defining the coalition’s limits and scope of action in accordance with the mandates agreed upon by the members. The groups who do not want to be publicly acknowledged would not likely be members of the coaltiion, as generally that requires publicly signing on to the coalition. However, the coalition could decide to have mandates that would allow for coordination with additional allies, precisely for tactical advantages - both for the coalition as well as for the groups desiring to "save face". Additionlly, the decision-making and communication processes with and to the members regarding this kind of coordination would be especially important to avoid "misinterpretations" that would impact the growth and sustainabiilty of the coalition to reach its action goals.

I hope others will add their thoughts and experiences.

Thanks --I hear you saying that we can make a distinction between coalition members and allies. Coalition members need to be out front, but they can still work with people outside the coalition with varying degrees of confidentiality. That make sense to me.

Here is a definition from a terrific overall resource - ABCs of Advocacy by Lina Alameddine and Cristina Mansfield arising from experiences in Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine.

Definition:

A coalition is a group of diverse organizations and individuals working together to pursue a single goal. Members join the coalition because they realize that the only way to solve the problem is by working together and benefiting from the power of numbers. In coalitions, all members make a commitment to share responsibilities and resources. Members are often from different sectors and have opposing views on an issue, which means they are more likely to experience conflict.

Benefits:

Coalitions allow us to share information, ideas, and resources with other organizations as well as distribute the risks and responsibilities of our advocacy campaign among members. In addition, coalitions offer us:

• Safety against threats

• Increased access to decision makers and other contacts

• Improved credibility and visibility

• An opportunity to broaden public support

• A chance to strengthen civil society and practice democratic processes.

Disadvantages

• the level of effort required by the coalition can distract our organization;

• uneven workload among members creates resentment;

• unequal power or resources can cause tension (a few powerful NGOs might dominate, even if NGOs with fewer resources have a lot to offer);

• the reputation of the other members may be adversely affected if one member has problems or behaves badly;

• the objectives of the coalition may require compromises that may not be acceptable to some members.

As a human rights-centered U.S.-based and -focused network, partnerships and collaborations are essential to how we work, and the human rights movement more broadly, the expansion of which is our mission. As human rights are interdependent and interrelated, we cannot afford to work in silos or on single issues without also recognizing the need to partner. The benefits to partnering and working in coalitions are that we expand our capacity, develop a stronger, more effective movement, and move closer towards deep, systemic changes. Partnerships are also important because when they are healthy and strong, they can be your life blood, e.g., those partners can be the ones to lend support when you are under attack, short on funding, or need additional support to continue the work.

But there are real challenges to developing healthy, strong partnerships. In particular, there can be issues of trust that must be overcome, especially when working with organizations or individuals who are directly impacted by human rights violations or grassroots, frontline organizations who are used to larger, more resourced organizations (or with more moderate, mainstream agendas) coming in and getting the attention, the resources, and the credit for the work they have been doing tirelessly and sometimes without pay. In many of those cases, there’s a history of exploitation and co-optation that must be acknowledged and a resulting trauma or distrust that must be built into how decisions are made, resources are allocated, credit is given, and work is distributed. Some of the questions I get from potential partners are how will they be acknowledged, what resources are available to support their involvement in the work, and how long do we plan to continue when the immediate goal is met.

Our approach has been to be transparent about our goals, what resources we bring, and how long we foresee the partnership lasting. It has also been particularly helpful to not expect our lower-resourced partners to bear equal share of the work when they don’t have the capacity to take it on, for us to take the backseat when it comes to publicity, and to openly acknowledge and position our partners as the experts they are. Another way we have been able to build trust is to create opportunities for partners that exceed the current partnership, for example, introducing them to other organizations within the network that support their work beyond our current goal and instituting capacity-building as an essential benefit we bring to the partnership.